A guest post by Manchester University’s Religious Studies course after their visit to the Labour History Archive & Study Centre

Christian Socialism began as a movement in the mid-19th century, around the year 1848. For early Victorian society, religion played a key part in their daily lives, whether it was to help navigate the seasons of the year and help with crop rotation in a rural setting or as an aspect of the daily life of an industrialist in the cities.

At its beginnings in 1848, Christian Socialism held 5 key principles:

- Opposition to competition.

- Christians to be active in society.

- Duty to help men (and women) out of poverty.

- Development of worker’s co-operatives.

- Importance of earthly salvation.

It is interesting to note that the actual Christian Socialist Movement collapsed in 1854 as an individual institution as people went their separate ways in the search for a fulfilment of their own political and religious ideals.

The emergence of non-conformist religion such as Methodism had a lot to do with the origins of the Labour movement. Early Methodism inspired many 19th century trade unionist movements. In many ways the beginnings of the Christian Socialist movement can be seen to translate into the modern day Labour Party with its support of the political order, its opposition to strike action and its rejection of class conflict. What’s more, many of the founders of what is now the Labour party were Christian socialists, such as Keir Hardie, who had been a lay preacher as a member of the United Secession Church. Many would be surprised to learn that the origins of the left wing party were Methodist rather than Marxist. However many recent Labour leaders, notably Tony Benn, Gordon Brown and Tony Blair, have been committed to Christian Socialism. Christian Socialists find inspiration through Bible passages such as: “Blessed are you who are poor, for yours is the kingdom of God’’ (Luke 6:20). This approach tends not to be revolutionary; rather it calls for improved conditions for the poor rather than radical societal change. Christian socialist ideology has moved popular religious movements and impacted the political landscape in Britain.

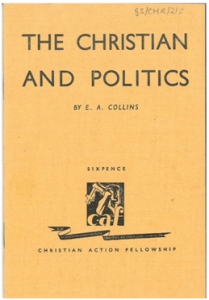

The Christian and Politics highlights the demand for effective Christian leadership. The opening paragraph of the booklet states that the Church has, for the past 100 years (1848-1948) been ‘urging Christians to take a more lively interest in politics and a more active part in national and international affairs.’ Many Christians of this time, the author notes, do not take into consideration their fellow men in relation to their religion, but rather between themselves and God alone. The author continues to encourage the readers; by identifying the ‘appalling apathy, indifference, ignorance and opposition amongst members of the churches’ and how ‘those who wield political power sometimes use it for selfish ends.’ In addition to this he proposes that it’s up to Christians to speak out the truth of God within the political world in order to work towards something greater.

The Christian and Politics highlights the demand for effective Christian leadership. The opening paragraph of the booklet states that the Church has, for the past 100 years (1848-1948) been ‘urging Christians to take a more lively interest in politics and a more active part in national and international affairs.’ Many Christians of this time, the author notes, do not take into consideration their fellow men in relation to their religion, but rather between themselves and God alone. The author continues to encourage the readers; by identifying the ‘appalling apathy, indifference, ignorance and opposition amongst members of the churches’ and how ‘those who wield political power sometimes use it for selfish ends.’ In addition to this he proposes that it’s up to Christians to speak out the truth of God within the political world in order to work towards something greater.

Today the Christian Socialism movement has re-branded as Christians on the Left. It is still an active movement with around 1500 members including 40 MPs. The group today still advocates many of the same principles and actions indicated in the 1948 pamphlet. For example, they believe that in political terms they do not have the “option to opt out,” and must instead be active as Christians in the political realm by taking part in campaigning, standing for election to local, regional, national and European bodies, political theology and parliamentary events amongst other things. However, although political action is at the heart of the Christian Socialism movement, both in 1948 and today, they are still keen to establish that their “primary identity is in Christ, not a political ideology.” It is therefore in their reading of scripture that they find both the justification and structure for their political activity.

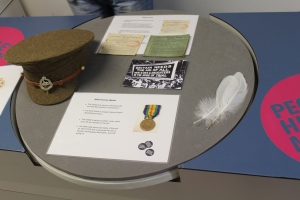

Arranging objects on the table was another thing I experimented with. Visitors aren’t too interested in looking at photographs and leaflets but wander towards medals and feathers. I found placing the less visually appealing items in the middle of the shiny things means eyes wander over them more often and visitors are more likely to eventually pick them up. Also, objects like ration books are easily ripped by little hands so the rule is tougher items at the front and more delicate ones at the back near the handler. Putting the solder’s hat and badge on an information sheet meant visitors had to pick up the hat to read the information and if they’ve picked up one object, they tend to pick up a few more. Crafty.

Arranging objects on the table was another thing I experimented with. Visitors aren’t too interested in looking at photographs and leaflets but wander towards medals and feathers. I found placing the less visually appealing items in the middle of the shiny things means eyes wander over them more often and visitors are more likely to eventually pick them up. Also, objects like ration books are easily ripped by little hands so the rule is tougher items at the front and more delicate ones at the back near the handler. Putting the solder’s hat and badge on an information sheet meant visitors had to pick up the hat to read the information and if they’ve picked up one object, they tend to pick up a few more. Crafty.

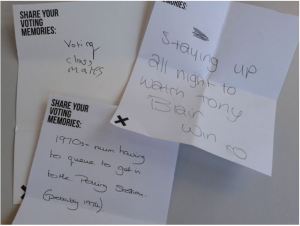

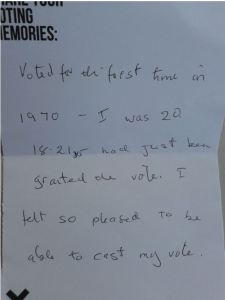

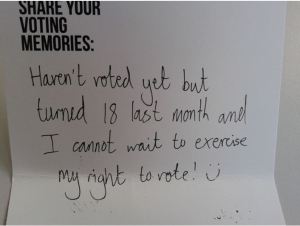

2013). It is refreshing to see a member of the young electorate dispel the myth that young people do not care to vote.

2013). It is refreshing to see a member of the young electorate dispel the myth that young people do not care to vote.